I made my first game!

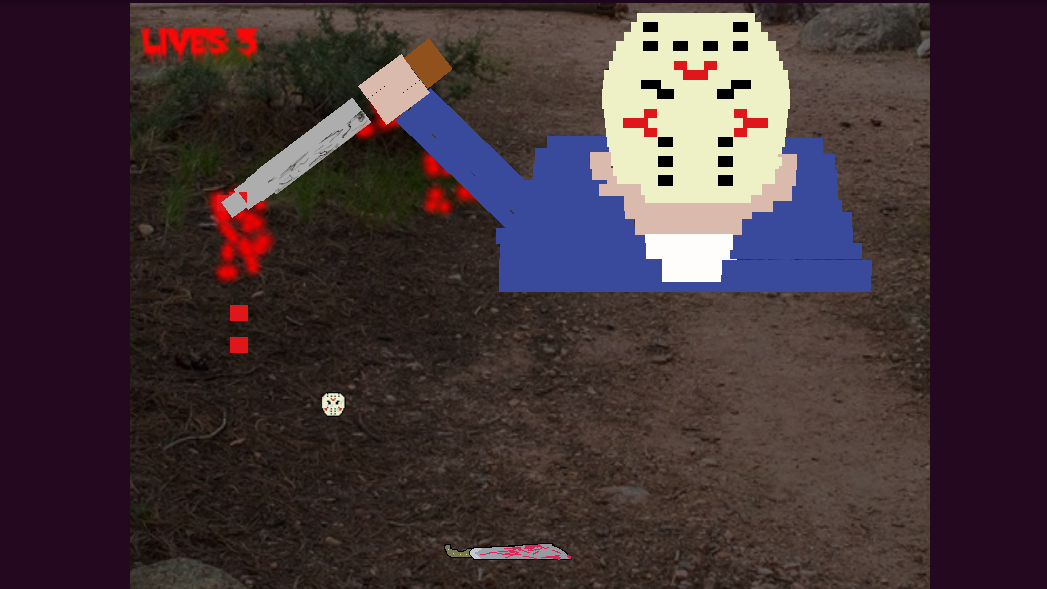

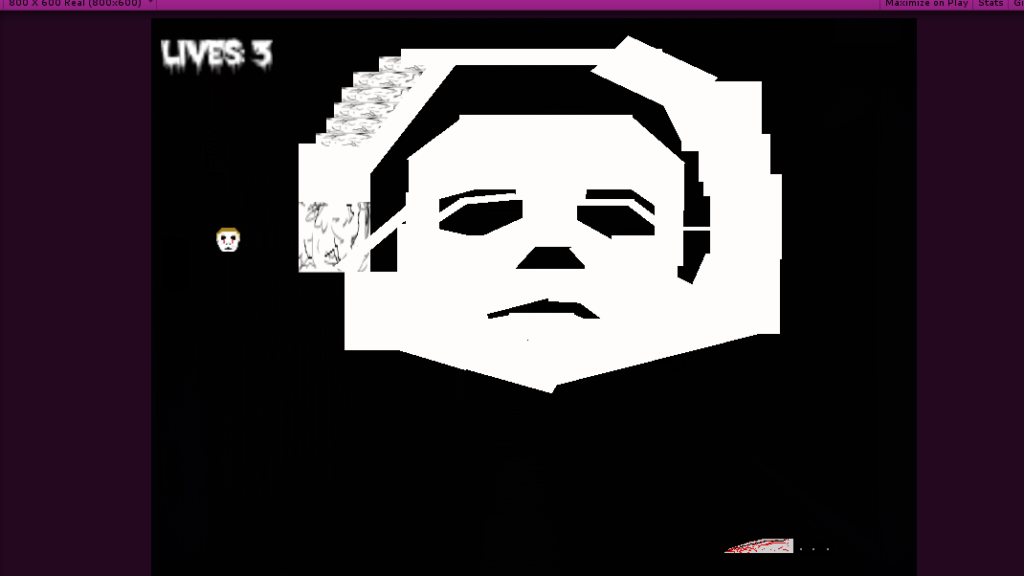

I’m pleased to announce that I finished making my first game, Horror Block Breaker. The coding, level design, artwork and playtesting are finished. All that remains is securing permission to use certain soundtracks for the levels which is easy to implement. Now that the journey is nearly complete and I can almost share the project with my fellow subscribers, I thought I’d take a moment to reflect and talk about what I learned in the process.

If you haven’t guessed from my blog posts, I’ve always wanted to make games and eventually go pro. At the advice of game developers I look up to, I enrolled in a course on Udemy.com teaching how to design games in Unity using C#. (I know it sounds like a bad pun, but bear with me). After learning how to make an Arkanoid mini-game, I decided to take the next step and expand on what I learned. What I thought would take a week ended up taking several months since I had to learn different coding mechanisms and how to draw pixel art. I never had any professional training in art or coding so everything I wanted to implement I had to teach myself on the fly. After a long four months of trying to make a small game while writing an E-book, I finally finished the game.

Admittedly it’s not ground-breaking, but it’s a step in the right direction. While making this project I’ve learned a few things that I thought might be helpful to people wanting to make video games. As you read this keep in mind that I’ve never had professional training and my advanced degree was in Japanese literature and translation, so I’m the last person who should be making something, but I did it! And if I did it, that means anyone can do it.

10 Lessons I learned while making a game

1. You must make everything and take responsibility for implementing your ideas.

If you ever made a mod or a game using a map editor or world builder such as what you find in Age of Empires, or Warcraft 3, you were spoiled. The beauty of those level designers is that the images and sprites have mainly been provided for you so you can instantly start placing units on a map and feel as though you’ve accomplished something within minutes. When it comes to Unity, you have to make every aspect from button presses, user interface, background images, the level editor itself, sounds, special effects, music, and gravity. It takes a lot of work, but once you’ve accomplished building the editor inside Unity and getting your prefabs all taken care of with a sprite canvas, you’re ready to hit the road. By the end of it, you’ll get this immense feeling of accomplishment.

2. Making a game by yourself can be very time consuming if you don’t have a plan or lack certain skills.

How many levels are there? How many different objects will be added? Do those objects need a sprite or image attached to them? How long do you want the game to be? How will the player interact with objects? What is the build order and how the player will get from the start screen of your game to the credits? What kind of scripts will you need to make? Do those scripts need adjustments?

Asking these questions and getting organized with how many levels you want, what you want to exist and identifying the components you need to code can really help. When I was designing Horror Block Breaker, I made a checklist of assets (monster sprites for the balls and paddles, scripts, game objects, and music) I planned to incorporate in the game and designed them one at a time.

Overall everything turned out to work well until I needed to learn how to code a life system, a timer, and other assets to make my game different from what I learned in the Udemy course. Learning how to draw and makeup for my lack of skills also took time. You can bring outside help, but that will likely cost money. Since this was a fun project I wanted to make for my YouTube subscribers and myself, I decided to make everything except the music due to the theme of the game.

3. Make a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and share it with people to get some feedback.

While I only made a few videos on my project, getting feedback from my YouTube subscribers really helped since they were honest. They told me whether or not the game was original, if the art was good or bad, and what they wanted to see changed. In the beginning I had an idea for the game, but wasn’t sure what people thought about it, so I asked my audience on YouTube for their thoughts based on showing them a level. I received nothing but positive feedback and went from there. If you have any sort of online audience, definitely get their feedback.

4. When starting out, keep your game design projects small.

Start smaller….Smaller than you think. I mean like 1 or 2 levels small if you’re a beginner when it comes to coding and art. I’ll be honest when I say that although my game only takes about 30 minutes to complete, I bit off more than I could chew for my first attempt. In my goal of trying to make my game unique with different shaped paddles, blood effects, monster-themed sprite balls, a life system, and a timer, I was jumping all over the place in my Udemy course. I was learning, but it was aspects of game design that were meant for the very end of the course. When I did learn it, I felt lost, confused, and out of place. Learning from my mistake, I plan to my next game much smaller and will focus on executing certain game mechanics well.

5. 1 hour of gameplay = about 100 hours’ worth of work.

I’ve heard this expression from developers many times. After struggling to make a basic arkanoid clone with unique aspects, I can say with confidence they were right. I worked on my game for about two hours per day sometimes more, and although my game is about 30 minutes in length, it took around 200 hours+ of work. This was because I had to design sprites, teach myself how to draw pixel art, research coding and make guesses outside of my course work. It also didn’t help that Unity’s game development documents weren’t complete, causing me to search in the depths of the internet for an answer regarding two lines of code.

6. No matter how good your code may seem, sometimes it just won’t work.

Originally, I had this idea of adding a game timer that would make a player score based on how quickly players would beat a level or die in the game. To accompany this, I also wanted to make a life system where players would gain a life after beating each level. After scouring the internet for documents and video tutorials, everything seemed to be going okay, but for some reason the clock would jump ahead between 20 – 45 seconds when you beat a level and your life counter would multiply by two! After a week of fiddling around not knowing or understanding what I was learning, and not progressing at all towards a finished product, I disposed of the timer and score system. I think that eventually I’ll get good enough to make those kinds of changes, but for now I’m pleased with where the game is at.

7. You have to be willing to let go.

Remember that time when you were working on something and you never felt satisfied with it? Maybe it was a term paper, a project, a piece of art, or a fun hobby where you’ll always find something you wish you could add to make your project better. But at some point you just have to let go. Had I kept my game smaller in scope by reducing the levels in half and not adding any form of a life system, the game would’ve been finished in two months instead of four.

8. Finding a social balance when you make games is important.

Making a game requires you sitting in front of a computer screen for hours on end and it can be lonely. It’s really helpful to have a social outlet, particularly an active one to get you recharged and to just escape from your dorm room, apartment, or house. Thankfully I had my frisbee group, board game group, and friends I could spend time with. Make sure you are getting exercise and social interaction.

9. There is no sole method to solve a problem or implement an idea in your game.

When I was trying to get my ball to position on the paddle when the player lost a life, I found what was close to 10 different ways of accomplishing the same thing. In this sense, coding can be compared to a spoken language where there are multiple ways to communicate a particular point across. In the end it is just a matter of preference. Some ways are easier and others are more difficult.

10. Remember to have fun!

At the end of the day, no matter how frustrated you become or how long it takes to implement something, you need to have fun making your game. When I got stuck working on a gravity glitch, I started fiddling around with different paddle shapes and 2D colliders. That fun little distraction gave me the idea of making unique paddles in each level. You never know when a spur of the moment experiment could lead to a new game mechanic.

I hope this article brought some insight for people wanting to make their first game whether its as a hobby or perhaps a professional app that makes money.